For nearly half a century, the 6,000 residents of the mid-Devon town of Okehampton did not have a proper railway.

Trains west to Plymouth ceased in 1968; a shuttle east to Exeter, which surprised everyone by escaping the Beeching axe, only lasted another four years. After that, it was mostly heritage trains, rather than proper passenger services.

Now, though, Okehampton is back on the network. Regular Great Western Railway services to Exeter began in November; in May, the frequency doubled, to hourly. Now, signs across Devon encourage passengers to explore the Dartmoor Line once again. At a time when, in the aftermath of Covid, the Treasury sometimes seems baffled by the idea we might need trains at all, it’s a comforting piece of good news.

Okehampton Station on the recently reopened Dartmoor Line

© a2b Global Media

The Dartmoor Line was one of the first routes to benefit from the Restoring Your Railway programme, first announced in January 2020 as a way of levelling up some of the poorly connected towns which had helped give Boris Johnson’s government its 80 seat majority. The British Railway network, which had been one of the most sprawling and extensive in the world, was famously cut to pieces in the 1960s, after the Beeching Report identified 2,363 stations and 5,000 miles of railway for closure. A few were saved; most were not.

All this has gone down in history as a terrible mistake which left many towns without rail access, as well as a deeply politicised process (the transport secretary who started it, Ernest Marples, had been managing director of a road construction business; at least one line, the Mid Wales, was saved because it ran through too many marginals). Little wonder, then, that a government which has staked so much on appealing to older voters’ nostalgia should promise to reverse some of it. We’re unlikely to see the return of the sort of extensive rural network that once covered places like Norfolk – some people, strangely, just really like cars – but the Dartmoor Line is unlikely to be the last to return.

So what else is on the agenda? Here are a few of the options.

East-West Rail

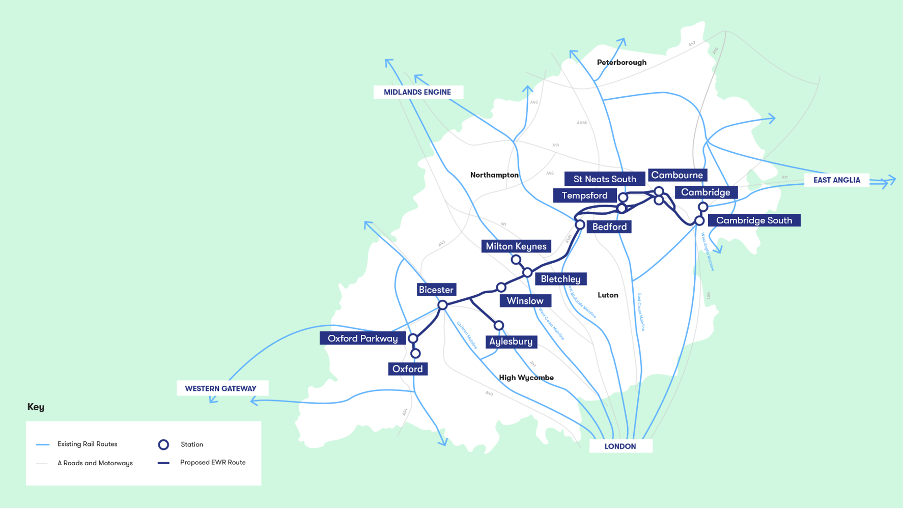

Historically known by the mildly sick-making name of the “Varsity Line”, this one linked Oxford and Cambridge via Bicester and Bedford. Although intended as an important strategic route through which both passengers and freight could bypass London, it was allowed to decline and closed to passengers in 1968: only the Bedford to Bletchley section remains as a branch line.

A map of East West Rail

In recent years, however, both Oxford and Cambridge have boomed, as has Milton Keynes, a new city incorporating Bletchley which, in a fantastic bit of joined-up thinking, was first established exactly 11 months before the line closed. So reinstating east-west services, to both improve transport and help solve the south’s housing crisis, has officially been a government goal since 2011.

The Oxford to Bicester bit reopened in 2016, and the stretch as far as Bedford should follow by the middle of the decade. The section from Bedford to Cambridge is more complicated, as people have built on much of it: that means it’ll require a new route, rather than merely new tracks, and the plan is not yet clear. If it is completed, though, it could allow for services from Hampshire and the Thames Valley all the way to East Anglia.

The Northumberland Line

What was the Blyth and Tyne Railway was another victim of Beeching, closing to passengers in the 1960s. But the line remained open to freight, and parts of it were incorporated into the Tyne & Wear Metro.

In 2020, the government announced plans to add stations to the line once again, to create a new (old) suburban service for passengers between Ashington and Blyth on the Northumberland Coast. It’s due to reopen in December 2023.

The Camp Hill Line

Another suburban route, this one through the plush south Birmingham suburbs of King’s Heath and Moseley. This one actually closed in 1941, as a “wartime economy”, and the impetus for reopening – due next year – has come largely from the West Midlands Combined Authority. So we can neither blame Dr Beeching, nor credit the Johnson government, for this one.

The Fleetwood Branch

But this one we can. The line, from Preston to Fleetwood, at the northern end of the Blackpool conurbation, closed in stages during the late 1960s. The Prime Minister pledged to reopen it on the campaign trail for the 2019 election.

Surely nobody would ever say that Boris Johnson is not a man of his word but the line remains closed, and there is no current plan to reopen it. It has at least made it through the feasibility study stage of the process and qualified for further investigation.

The Dartmoor Line, Again

This once, remember, provided an alternative route between Exeter and Plymouth. The case for such a route has become much clearer since February 2014, when a storm destroyed the sea wall at Dawlish, just south of the former, effectively cutting most of the West Country off from the rest of the network.

So extending the route west from Okehampton would ensure that trains from Plymouth and Cornwall can still reach the rest of the country, whatever the weather.

The main line at Dawlish, which runs right by the sea

© a2b Global Media

***

Something to note here: none of these lines are in or around London. The East-West rail is the closest, but that would link the outermost of outer commuter towns.

This probably reflects the fact London was largely spared the Beeching axe. Then again, maybe it means something else. This entire programme, remember, was aimed at the voters a long way from the capital who’d backed this incarnation of the Tory party, which has encouraged the government to conduct no fewer than 38 different feasibility studies.

That, though, looks a lot like jam spreading: unless there is a pretty radical shift in approach at the Treasury, there simply won’t be that much capital to go around. Not every town will get its trains back.

About Jonn Elledge

Jonn Elledge is a journalist and editor who specialises in transport and local government. Former assistant editor of the New Statesman.

Comment

by Jonn Elledge

Published

12 Jul 2022

Tags

Comment

United Kingdom

For nearly half a century, the 6,000 residents of the mid-Devon town of Okehampton did not have a proper railway.

Trains west to Plymouth ceased in 1968; a shuttle east to Exeter, which surprised everyone by escaping the Beeching axe, only lasted another four years. After that, it was mostly heritage trains, rather than proper passenger services.

Now, though, Okehampton is back on the network. Regular Great Western Railway services to Exeter began in November; in May, the frequency doubled, to hourly. Now, signs across Devon encourage passengers to explore the Dartmoor Line once again. At a time when, in the aftermath of Covid, the Treasury sometimes seems baffled by the idea we might need trains at all, it’s a comforting piece of good news.

The Dartmoor Line was one of the first routes to benefit from the Restoring Your Railway programme, first announced in January 2020 as a way of levelling up some of the poorly connected towns which had helped give Boris Johnson’s government its 80 seat majority. The British Railway network, which had been one of the most sprawling and extensive in the world, was famously cut to pieces in the 1960s, after the Beeching Report identified 2,363 stations and 5,000 miles of railway for closure. A few were saved; most were not.

All this has gone down in history as a terrible mistake which left many towns without rail access, as well as a deeply politicised process (the transport secretary who started it, Ernest Marples, had been managing director of a road construction business; at least one line, the Mid Wales, was saved because it ran through too many marginals). Little wonder, then, that a government which has staked so much on appealing to older voters’ nostalgia should promise to reverse some of it. We’re unlikely to see the return of the sort of extensive rural network that once covered places like Norfolk – some people, strangely, just really like cars – but the Dartmoor Line is unlikely to be the last to return.

So what else is on the agenda? Here are a few of the options.

East-West Rail

Historically known by the mildly sick-making name of the “Varsity Line”, this one linked Oxford and Cambridge via Bicester and Bedford. Although intended as an important strategic route through which both passengers and freight could bypass London, it was allowed to decline and closed to passengers in 1968: only the Bedford to Bletchley section remains as a branch line.

In recent years, however, both Oxford and Cambridge have boomed, as has Milton Keynes, a new city incorporating Bletchley which, in a fantastic bit of joined-up thinking, was first established exactly 11 months before the line closed. So reinstating east-west services, to both improve transport and help solve the south’s housing crisis, has officially been a government goal since 2011.

The Oxford to Bicester bit reopened in 2016, and the stretch as far as Bedford should follow by the middle of the decade. The section from Bedford to Cambridge is more complicated, as people have built on much of it: that means it’ll require a new route, rather than merely new tracks, and the plan is not yet clear. If it is completed, though, it could allow for services from Hampshire and the Thames Valley all the way to East Anglia.

The Northumberland Line

What was the Blyth and Tyne Railway was another victim of Beeching, closing to passengers in the 1960s. But the line remained open to freight, and parts of it were incorporated into the Tyne & Wear Metro.

In 2020, the government announced plans to add stations to the line once again, to create a new (old) suburban service for passengers between Ashington and Blyth on the Northumberland Coast. It’s due to reopen in December 2023.

The Camp Hill Line

Another suburban route, this one through the plush south Birmingham suburbs of King’s Heath and Moseley. This one actually closed in 1941, as a “wartime economy”, and the impetus for reopening – due next year – has come largely from the West Midlands Combined Authority. So we can neither blame Dr Beeching, nor credit the Johnson government, for this one.

The Fleetwood Branch

But this one we can. The line, from Preston to Fleetwood, at the northern end of the Blackpool conurbation, closed in stages during the late 1960s. The Prime Minister pledged to reopen it on the campaign trail for the 2019 election.

Surely nobody would ever say that Boris Johnson is not a man of his word but the line remains closed, and there is no current plan to reopen it. It has at least made it through the feasibility study stage of the process and qualified for further investigation.

The Dartmoor Line, Again

This once, remember, provided an alternative route between Exeter and Plymouth. The case for such a route has become much clearer since February 2014, when a storm destroyed the sea wall at Dawlish, just south of the former, effectively cutting most of the West Country off from the rest of the network.

So extending the route west from Okehampton would ensure that trains from Plymouth and Cornwall can still reach the rest of the country, whatever the weather.

***

Something to note here: none of these lines are in or around London. The East-West rail is the closest, but that would link the outermost of outer commuter towns.

This probably reflects the fact London was largely spared the Beeching axe. Then again, maybe it means something else. This entire programme, remember, was aimed at the voters a long way from the capital who’d backed this incarnation of the Tory party, which has encouraged the government to conduct no fewer than 38 different feasibility studies.

That, though, looks a lot like jam spreading: unless there is a pretty radical shift in approach at the Treasury, there simply won’t be that much capital to go around. Not every town will get its trains back.

About Jonn Elledge

Jonn Elledge is a journalist and editor who specialises in transport and local government. Former assistant editor of the New Statesman.