At some point in the first half of this year – the powers that be are refusing to be any more specific than that – Crossrail will finally open.

The single biggest addition to London’s rail network in decades, it’ll speed passengers under the capital at a dizzying 90mph, linking Paddington to Canary Wharf in just 17 minutes, and providing a whole host of new connections between east and west London, Essex and Berkshire.

The thing is, though, the Elizabeth Line, as the new link is horrifyingly named, has been on the table for a very long time, and taken many different forms. The scheme finally won approval in 2008, but the first serious proposals date to the early ’90s, the first appearance of the word “Crossrail” to the 1974 Central London Rail Study. Even by then the concept was an old one: as far back as the 1840s, the very earliest years of the railways, the company behind the Regent’s Canal from Paddington to Docklands had taken to wondering if this had actually been a stupid time to get into the canal building business, and whether they might not be better off draining it and sticking some tracks at the bottom.

The myriad, unbuilt Crossrails down the decades mean that vast numbers of places to the east or west of London have at some point been under the impression that the new link would be serving them. So here are a few of the places that Crossrail won’t go. In the name of sanity, I’m going to stick to places that did come in for serious consideration at some point or another – although as the piece goes on you may notice them becoming gradually less and less plausible.

1. Old Oak Common

First up, one that’s actually going to happen. The closed railway yards at Old Oak Common, together with the neighbouring Park Royal, make up one of the largest regeneration sites in inner London, with room for 24,000 homes across 650 hectares. A key part of the plan is a huge new station, with 14 platforms on the Great Western Mainline and HS2, and links to new platforms on the Overground, too.

If all goes to plan, it’s due to open in 2026, even if the high-speed line won’t follow for a few years after that. Very much the Stratford of West London.

2. North Kent

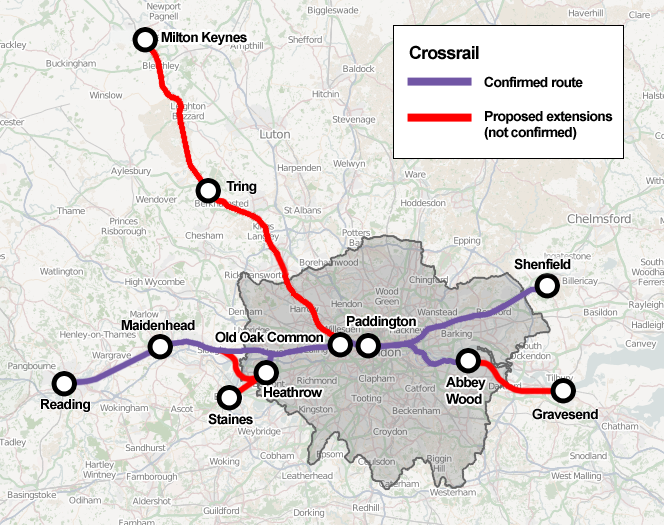

Probably the most likely extension that isn’t literally being built right now would see the south-eastern branch extended east from Abbey Wood through Dartford, before terminating at either Gravesend or possibly Ebbsfleet, where there’s a Eurostar station and potential for a lot of new housing. This one almost made the grade in the early 2000s, but was dropped from the plan and its route safeguarded. It does have the support of the mayor, bringing as it does TfL services to a chunk of south east London currently largely deprived of them.

The one slight problem is that the North Kent line is already complicated enough, with its track shared by Southeastern and Thameslink and with multiple possible routes to reach Dartford. The idea of entirely separate Crossrail tracks has been discounted as unaffordable, but any Crossrail extension along the existing route is surely going to mess with service patterns closer into London. We’ll see.

3. The West Coast Main Line

One of the oddities of Crossrail as built is that it’s unbalanced. As many as 24 trains per hour are expected to run through the central tunnel from the eastern branches; but only 12 will continue west of Paddington. This seems like something of a waste.

So in 2011, Network Rail recommended that a short section of track be added running from Old Oak Common to join the West Coast Main Line, allowing those terminating trains to take over some of the regional services between Hertfordshire and London Euston. The government briefly backed the plan in 2014, although it was unclear whether Crossrail services would run all the way to Milton Keynes or terminate at Tring. By 2016, this question no longer seemed to matter because the whole idea had been scrapped as poor value for money.

Bit of a shame, that, but since the Paddington problem remains, it must be at least possible that something like this scheme will one day rear its head again.

4. Aylesbury

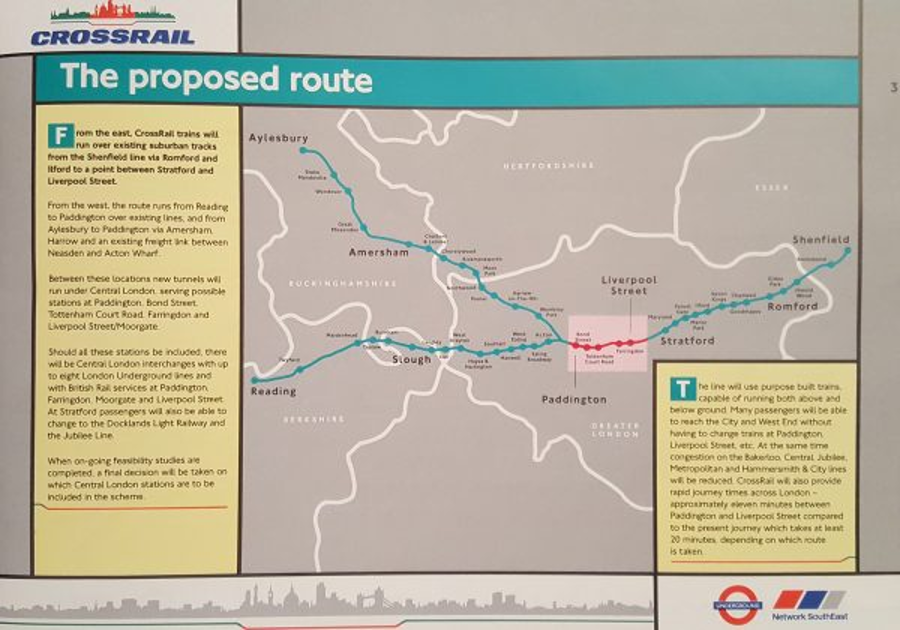

The ’90s version of the scheme, which I remember fondly from the leaflets that appeared at Gidea Park station back when I was a baby nerd, didn’t serve Heathrow (which had yet to get a rail connection) or Canary Wharf (which was still, bafflingly, seen as something of a white elephant).

It did, though, have a second western branch, which would have headed to Wembley before swallowing the Chiltern suburban route to Harrow, Amersham and Aylesbury. This seems a bit baffling in retrospect – much of this route is already served by the Metropolitan line; surely it didn’t need another route across town to Liverpool Street? – and this scheme was in any case dropped in 1994. When Crossrail reared its head again in the early 2000s, Chiltern council said it’d rather have upgrades on the existing route thank you very much.

And so, that was that. Bit of a shame if you’re Wembley Stadium, but perhaps perfectly understandable for everyone else.

5. Richmond

With Aylesbury out of the picture, the people planning the scheme in the early 2000s considered a new south western branch. This would also diverge from the mainline somewhere round Old Oak Common and then, via either the North London line or a new tunnel, swallow the Richmond branch of the District line, before continuing on to Kingston and Norbiton.

This would have done wonders for a part of south west London that lies beyond the tube – but it would also have meant diverting the North London line to Hounslow, doing a load of building work in suburban Kingston, and messing up the South West Rail network something chronic by forcing it to share space with Crossrail trains. As if that weren’t enough, a bunch of ungrateful people in places like Kew seemed miffed at the idea of losing their District line connection, even though the District is so slow that anyone using it is well advised to carry a pillow.

And so, before the scheme ever reached Parliament, that was dropped as well.

6. Staines

One of those long-standing privately promoted projects that somehow never seems to get anywhere is the “Heathrow Southern Rail Link”: a new tunnel running south of the airport to connect to the South West Trains and allow services to the airport from Surrey, Hampshire and so on.

There’s little sign of this actually becoming reality – BAA, it turns out, are quite happy with a rail link to London, and are less fussed about one towards Portsmouth. But as part of his efforts to promote the plan, in 2016, Heathrow Southern Railway’s chief executive Chris Stokes told Modern Railways magazine that the line could also allow an extension of the Elizabeth Line to Staines. Which would of course be brilliant for the people of Staines.

7. Cambridge, Stansted, Ipswich, Basingstoke, Northampton, Guildford et al.

In 2004, the year before the bill for Crossrail finally made it to parliament, a coalition of senior rail executives promoted a different scheme. Superlink would have featured a very similar tunnel – but instead of serving stations in outer London and the inner commuter towns, it would have swallowed regional services to destinations across the east and south east of England.

The result would have been something more like Thameslink, a network focused on longer-distance services rather than a jumped up tube line. This, its promoters argued, would carry four times as many passengers and require much less public subsidy.

The proposal was rejected – partly because it would have required politically contentious construction on the metropolitan green belt; partly because serving such a wide range of destinations would mean a signal failure in, say, Ipswich could delay services right across London, making it a poor fit with the idea of tube-frequencies beneath the city centre.

These critiques may well have been true. But it’s hard not to notice that they came from Cross London Rail Links, the body set up to plan and promote the new scheme, which was at that time a joint venture between Transport for London and the Department for Transport. (It later became Crossrail Ltd.) It’s just possible that it had its own institutional reasons for preferring to focus on Londoners, rather than the good people of Hampshire or Suffolk.

8. Southend

One of the more transparent proposals to do the rounds of late would see Crossrail extended east from Shenfield, through the Essex commuter belt on to Southend Victoria. This would enable the line to serve Southend Airport station, potentially enabling London’s growing airport capacity needs to be partially solved there and relieve Heathrow.

The proposal has, unsurprisingly, attracted the support of Southend council, but has no central government backing whatsoever. What’s more, it seems to be promoted entirely by Stobart Aviation, who – would you believe it? – just happen to own Southend Airport! Can’t blame them for trying, I suppose.

The line we’re actually getting will connect 41 stations in London, Berkshire and Essex, from Reading or Heathrow in the West to Abbey Wood and Shenfield in the east. That’s pretty cool – but when it opens, and other commuters and their political representatives realise quite how quick it is, don’t be surprised if the pressure starts to build to add more.

About Jonn Elledge

Jonn Elledge is a journalist and editor who specialises in transport and local government. Former assistant editor of the New Statesman.