Until recently, a major English city had no direct rail services to or from the capital. To get to Middlesbrough from London – as I foolishly did, one freezing day in November 2017 – you had to go to Darlington, also in the Tees Valley but a good 13 miles to the west, and change to a local train.

This seemed, considering that nearly 200 years ago the Tees Valley was home to the first steam passenger railway in the world, just a tiny bit unfair. But then, last December, all that changed: LNER launched the first passenger service between Middlesbrough and London in more than 30 years, and justice was restored.

This story raises a question. With Middlesbrough now sorted, and Bradford glorying in Grand Central services since as far back as 2009, what’s the biggest city in Great Britain that still cannot be reached on a direct train from London?

This question, like all the best questions, instantly runs aground on matters of definition. The words ‘London’ and ‘direct train’ are clear enough, but both ‘city’ and ‘biggest’ are contested.

‘City’ first. Officially, there are 65 settlements on this island with city status: that number is due to rise to 70 before the year is out, thanks to the fact five more (Colchester, Doncaster, Dunfermline, Milton Keynes and Wrexham) are being added to the list to celebrate the Queen’s Platinum Jubilee. All that said, though, city status is completely ridiculous and bears no relation whatsoever to actual settlement size, as you can tell by looking at some of the minuscule places that already have it (St Asaph? Ely?).

If we’re looking for the biggest, then, we’re better off starting with population size. But there, too, there are problems: often the population figures you’ll find on Google are those of council areas, and these too can be absurd. Some leave out most of the suburbs (such as Manchester); others include vast areas of countryside (such as Bradford; which is, confusingly, from some perspectives part of Leeds). You could look at built-up area population, instead, but that’s harder to get hold of, and anyway just means someone, somewhere, ends up arguing about whether a slight gap in the street plan turns somewhere into more than one place or not.

If that doesn’t work, you could look instead at metropolitan area population – essentially, the commuter belt. But London’s commuter belt covers much of the south east of England, and since it’s direct trains to London we’re interested in here that’s going to get very weird very fast.

So we can, at best, be vague about this. And while there are a number of options, most of them are problematic.

Birkenhead doesn’t have direct trains to London – it did once, to, unexpectedly, Paddington – and even if it’s only home to around 90,000 people, it is part of an urban area with over 300,000. It is, however, essentially a part of Liverpool (come on, guys, it really is), and even if the Mersey is in the way Lime Street station is only a few minutes from Birkenhead Central by the frequent underground Merseyrail. So that seems silly.

We can dismiss Salford, just up the road from Manchester Piccadilly, on similar grounds. Some of Greater Manchester’s outer suburbs – Bolton (140,000), Oldham (96,000), Rochdale (108,000) – are better candidates. But my unpopular opinion is that they’re no more separate from Manchester than Croydon is from London. So I’m not counting those either.

Barnsley (91,000) probably is sufficiently separate from Sheffield to count, and Huddersfield (163,000) is almost certainly separate enough from Leeds. But the latter arguably falls because, even if you can’t get trains to London from the centre, you can from Mirfield or Brighouse in what are effectively in its suburbs.

So that leaves Barnsley fighting it out with four other small cities and/or large towns: Blackburn (121,000), Burnley (73,000), Mansfield (107,000), and Telford (143,000). One of those is clearly the biggest. And so, surprisingly, the largest settlement on the island of Great Britain without direct trains to London is the Shropshire new town of Telford.

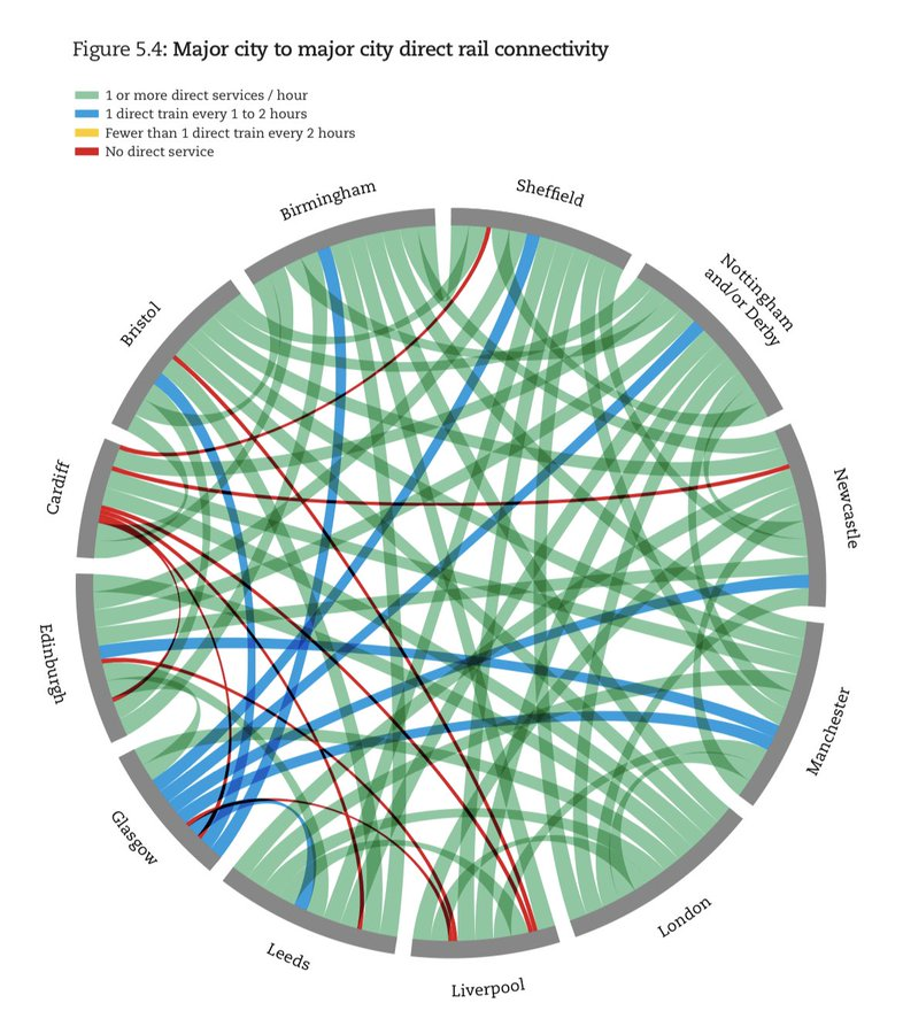

This suggests that, just maybe, our rail network is perhaps not quite as bad as we sometimes like to think. Here’s a lovely graphic from not-for-profit research group Greengauge 21, showing which of the big cities do and don’t have direct trains as of 2018:

It shows that, before the pandemic at least, the city-to-city connections were surprisingly decent. London connects frequently to all these cities, of course – they’re all quite a lot bigger than Telford – but Manchester, Birmingham and Nottingham/Derby connect to all of them, too, albeit less often. Where connections are missing, it’s generally to cities that are geographically slightly more peripheral: Glasgow, Liverpool, Cardiff.

All that said, though, the fact Liverpool Lime Street is at the end of a line hardly feels like enough of an excuse to force everyone to trek to Greater Manchester if they want to get to Scotland or Wales. And even where direct connections do exist, they’re sometimes annoyingly slow: just try getting the three-hour stopping service from Manchester to Cardiff.

It’s great they got that London-Middlesbrough train sorted. But c’mon, chaps. We can do better than this.

About Jonn Elledge

Jonn Elledge is a journalist and editor who specialises in transport and local government. Former assistant editor of the New Statesman.