Population growth and infrastructure growth go hand-in-hand, with one alternately leading the other. While infrastructure improves, transporting people and goods, it stimulates new residential and industrial development, which in turn stimulates infrastructure development. And so it is that our green continent has been dissected into ever smaller areas by arterial routes. Conservation areas such as nature reserves and protected wildlife sites have been reduced to areas too small and too isolated to sustain the very wildlife they were established to protect.

Without taking mitigation measures, landscapes may be affected to varying degrees by this fragmentation. Forests, for example, can suffer a reduction of biodiversity by up to 75%. This has been understood for decades, for example in the Amazon Rainforest. Less glamourous areas of wildlife conservation are equally at risk: woodlands, mountains, plains and riverbeds all suffer when great tranches of human infrastructure run through them. The eco-diversity is impacted, and while it might not be as dramatic as introducing rabbits to Australia, the changes they cause are detrimental and irreversible.

The three leading causes of fragmentation are transportation, agriculture and urbanisation. Transportation not only creates a physical barrier between areas of wildlife protection , thus blocking migration corridors, it also creates noise and light pollution as well as air pollution. In addition to the hundreds of thousands of dead animals littering the verges of European roads and railroads, flora mortality is also an increasingly serious problem.

Lesser of Some Evils

It is not just railways and roads that cause this fragmentation; canals, pipelines, electricity and telephone networks bisect the countryside, but it is railways and roads that cause the most direct threat to wildlife by way of collisions with animals trying to move across tracks and roads, with a Spanish study estimating that high-speed trains kill 36 animals per kilometre a year, as well as the various pollutions they emit and more subtle impacts such as water runoff and soil erosion, which also comes under the bracket of habitat degradation.

However, railway lines are less damaging than roads to both flora and fauna. They are narrower and therefore take up less physical space and they are more easily elevated to allow animals to migrate beneath. In addition, the nature of a railway track is such that it is dry. Ballasts filter water runoff and drainage ditches limit the flow of water and erosion and sediment erosion. Other measures that can be easily taken to mitigate against fauna mortality by collision with trains are fauna passageways and wildlife-fences along the lines, which may also reduce noise pollution.

An International Solution

The specific issue of habitat fragmentation somehow went unnoticed in Europe by all but environmental groups until 1998, when COST 341 Action was established to enable European countries to work in collaboration, developing a greater understanding of the problem and exchanging ideas and best practice.

The European Cooperation in the Field of Scientific and Technical Research (COST) recommends that an ecologically sustainable transport infrastructure requires innovation and adaptability to various landscapes, be they mountains, forests, rivers or plains. It also points out that this is an issue that must be addressed at a policy level in order to create an interdisciplinary approach to solve the problem; politicians, economists, ecologists, engineers, landscape architects, planners and the general public must all be involved in order to ensure the on-going survival of conservation areas.

COST 341 Recommendations

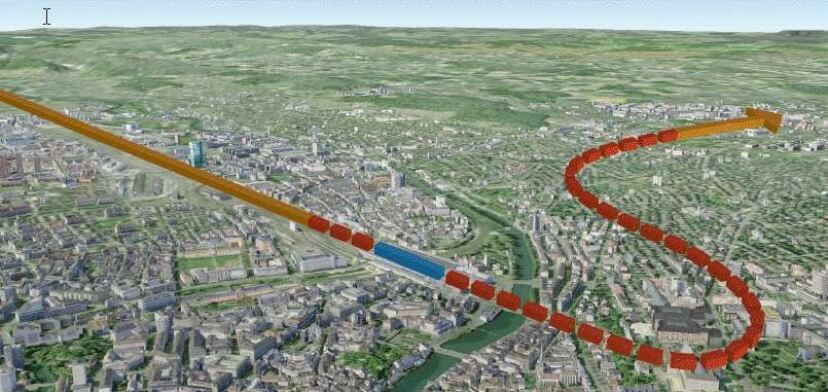

Avoidance is the first cure; the route should be plotted in sympathy with areas of natural interest, minimising the use of preserved land as much as is practicable. The Netherlands is particularly good at this, despite a huge investment in rail and road infrastructure over the last decade.

Where the route cannot be changed, however, certain measures may mitigate against the damage a railroad might cause. If engineers and surveyors approach the construction from the point of view of avoiding fragmentation as much as possible, then it can be minimised and animal habitats and populations can remain connected. Fauna Crossings, which take the form of overpasses and underpasses, are very successful in the preservation of large animals. Smaller animals can be protected by the adaptation of underpasses to allow for migration beneath the lines at more regular intervals.

These measures can also be fitted retrospectively, although at a greater cost than if they had been fitted during the initial construction process. It is therefore recommended that these measures be considered during the planning phase, not least since COST 341s recommendations are likely to be adopted as EU Regulations in the coming decades.

A further measure which mitigates against the damage caused by railroads is the compensation, construction or restoration of existing habitats. This can take the form of constructing a new preservation area away from the railroad, or extending another pre-existing preservation area in the hopes that the wildlife endangered by the railroad will migrate in that direction.

However, this is the least effective of the measures; the value of new, engineered habitats is not as great as that of established, natural ones and they very rarely enjoy as great a range of biodiversity. Therefore, the most effective solution is to plot a route which avoids areas of natural interest.

The Angle of Approach

The best way to mitigate against habitat fragmentation is in the planning stages. Running a new railway close to an existing road or canal, or even a pre-existing railway, limits the damage by simply not creating yet another cleaved line across the countryside, and this is where policy makers most often clash with environmentalists.

On this basis, the European Union has issued Directives which require environmental impact assessments to take place in all planning documents. These do not, however, bind a government or company to take action based on the results of that assessment.

The strongest of the European Legislation on the matter is Council Directive 92/43/EEC on the Conservation of Natural Habitats and of Wild Fauna and Flora; although requiring Member States to record and maintain natural conservation areas, it allows that their destruction may be allowed if a plan or project [may] be carried out for imperative reasons of overriding public interest, including those of a social or economic nature. It provides that the Member State has to take compensatory measures to ensure that the environment isnt completely overlooked in the advancements of human interests.

As such, many European projects are able to pass through areas of natural interest and preservation, but by taking measures to mitigate, such as by the creation of fauna overpasses and underpasses and by relocating areas of natural interest, the projects can go ahead. As a last resort, moving the preservation area is an option, but it is the least desirable. It is obvious that urban planning will diminish natural habitats; what is less obvious is the impact infrastructure growth has on natural environments. As such, infrastructure projects must take the preservation of fauna and flora into account as one of their primary considerations.