We Need to Level With You – Stop, Look and Listen Is Not Fit for Purpose

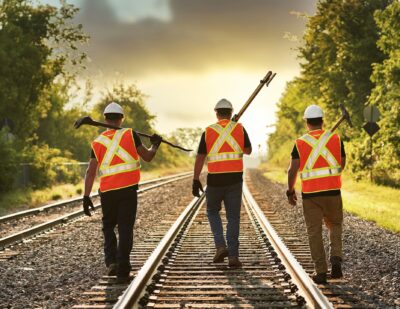

We’ve run a number of stories about level crossings lately. Stories about new audible warning devices installed by Network Rail in the UK to make level crossings ‘safer’, about Network Rail’s Signly app to support people with visual, hearing and / or mobility impairments navigate level crossings, about International Level Crossing Awareness Day, stories about Union Pacific’s outreach efforts after the US Department of Transportation found 94% of public railroad crossing accidents were the result of risky driver behaviour. The US DOT launched a campaign called “Stop! Trains Can’t!” to help reduce the number of fatalities. We received a lot of comment on this last news item in particular so we decided to delve further into the level crossing world and find out the lay of the land. We spoke to Martin Gallagher, the UN Safety Committee Chair & Director Global Level Crossing Services. Here is what he said:

Railway-News: Do you want to start by introducing yourself and give us some background information? How are you involved with level crossings?

Martin Gallagher: I was Head of Level Crossings for Network Rail for 3 years; Network Rail is the biggest rail infrastructure manager in Great Britain, and one of the largest in Europe. And from that, I also chaired the United Nations Experts Committee on Level Crossings and Level Crossing Safety. I’ve done that for 4 years, and have been working as an adviser or consultant to a whole range of infrastructure managers and system developers across the world, helping them to develop systems to reduce risk, improve safety and improve performance at level crossings internationally.

RN: There are roughly 6,000 level crossings in the UK. Starting from a sceptic’s perspective, what’s the main issue? The number of level crossing deaths in a year in the UK was recently reported as 2. Why should I be concerned that they are a problem to begin with?

MG: If you look at these issues solely in terms of the number of fatalities, yes, the numbers are currently low, and very low compared to road deaths. People always confuse level crossings with safety concerns. There are safety concerns, but one of the reasons to be concerned is the level of demand for rail across the world. In the UK demand is rising by something like 7% per year. The demand for road and the volume of vehicles are increasing also. The latest polling from the Department for Transport in the UK for example suggests that the number of vehicles will double by 2040. So we have a simple equation: more trains, more people, more passengers, more people using roads and growing populations. And the one place that all of them intersect in the railway is at level crossings. So the reason why people should be concerned is because with demand growing on all sides, level crossings are a bottleneck and tens of thousands rail crossings across the world are not equipped for large numbers of users.

RN: Is this primarily an efficiency concern of traffic coming to a halt at level crossings or a safety concern?

MG: Those things are interdependent. If you look at the type of level crossings in the UK, fewer than half of the level crossings are protected by audible warnings, lights and barriers and the majority have no protection at all. They are simple trails across the railway or gates that open on to the railway with no signalling, and no controls other than the ‘Stop, Look and Listen’ sign. The unprotected level crossings may have speed restrictions imposed on them, because they have sighting and safety concerns. If you keep multiplying these up and saying, ‘We’re going to have more trains using those lines,’ then you’ll change the risk; it creates a greater risk, which will create more human factor issues, more accidents, more delays and congestion. These crossings are not fit for purpose now let alone for more usage.

RN: If a rural level crossing becomes an urban one, then obviously you would have to adapt the level crossing to cope with the added demands. Is there not a measure then that works that we already have? We could just make the unprotected ones be like the protected level crossings that we already have, surely?

MG: That’s unaffordable. There currently are very few affordable solutions to address this problem. And that’s part of the issue. The business case at the moment to improve the levels of protection at all of these unprotected crossings, only creates a small amount of spend. The cost of installing warning systems at level crossings, for Network Rail or anybody else, is tens if not hundreds of thousands of pounds, occasionally millions where resignalling is required. There simply isn’t the funding at the moment to increase protection. But that’s also assuming that there are solutions out there. There are also not very many solutions because of another massive issue, namely the supply chain issue with Network Rail, in this country. The development from concept to market, from concept to operation, the development cycle will take at least three years and the risk is with the developer.

That adds a huge amount of cost into your eventual product and means that the majority of the small innovative companies that are agile and can deliver things or offer solutions at lower costs may drop out. They can’t afford to take the risk. They can’t afford long development cycles, where they’re not guaranteed to sell a single unit. So for solutions with the level of safety integrity required to meet challenging technical specifications you’re left with a much smaller number of larger companies who then develop relatively expensive solutions that Network Rail can’t afford to put into 90% of unprotected crossings; Therefore you have this vicious circle where what you’re left with is crossings that remain unprotected and a frustrated supply chain.

RN: Everything remains as it is because there’s no ideal way forward.

MG: There is an ideal way of moving forward but it requires lots of different changes. 5-year funding cycles are not ideal when trying to plan a long-term strategy. Yes, you can make some longer-term policy statements but that’s different to a funded strategy. The pace of innovation means it is difficult to develop a solution and implement that and then measure the effectiveness in order to demonstrate the business case to the regulator for more funding next time around to continue into the next control period. And delivery of new schemes effectively stops for the last 18 months of each control period as work has to be completed within that control period. Suppliers also want to know what the market opportunity is before committing. All too often the figures and volumes are too vague. This stifles genuine innovation.

RN: How does the rail regulator come into all of this?

MG: The rail regulator sets deliverables and can make recommendations that Network Rail are required to deliver unless they can come up with a justifiable reason not to. The rail regulator can look at an issue like unprotected rail crossings and say a variety of things to Network Rail, “The technology exists to provide a reasonably practicable automatic warning system” or after an investigation ‘We’re giving you a recommendation that says that you will implement some kind of warning system or…’ whatever the specification is. All of these things are solvable. If you believe that exposing elderly people and children to trains travelling at 100mph and asking them to judge the speed of that train before crossing is the best we can do, I’d have to disagree.

RN: What does the rail regulator say at the moment? Do they believe it’s not an issue and it won’t be an issue, they’re not convinced? What is their standpoint?

MG: The rail regulator recognizes that it is an issue, but also recognizes that there’s limited spending. They feel that, ‘Yes, in a perfect world, having unprotected crossings isn’t ideal. Network Rail are trying to do something about this but too clumsily and slowly.’

In this country, Network Rail have over 1500 crossings that are protected by a whistle board. This is where the means of protection and the crossings are inherently unsafe. There isn’t enough time at many of these crossings. The time it takes to traverse a crossing is more than the time there is between when you first see the train and the train arriving. So a train driver is required to sound a horn to warn that a train’s approaching. There are so many points of failure in that process that Network Rail have a presentation on it.

RN: That’s a quarter of the crossings in the UK. You would imagine there would be much more in the way of accidents, surely?

MG: At these crossings a train driver has to sound his horn, and the person standing on the crossing, maybe hearing impaired, walking the dog on the crossing is supposed to be able to hear that without seeing the train and to recognize that that means there’s a train coming; Network Rail themselves admit that this is an ineffective warning system or protection system. But the rail regulator appears quite prepared for Network Rail to now put out a development tender opportunity to the supply chain to say, ‘Over the next three years, we want to address this issue and by 2025 we want all of these whistle boards removed.’ Well, that means we’re not going to see improvements for at least three years. And I understand what you’re saying about ‘Why aren’t there more accidents?’ The only explanation I can give is, people must be good at avoiding being hit by trains. Because you would not let your child or your elderly parents use those crossings if you knew that the time to traverse them is less than the time available once you could see a train.

RN: How much time would I have to get across one of these crossings?

MG: That depends on the crossing, but the science behind it is all so assumptive. How quickly can people walk? Who is using the crossing? When are they using it? What are they doing whilst they’re using it? Do they know what they are supposed to do? Furthermore, I have been approached by contractors recently who have been awarded work to carry out risk assessments at level crossings. They didn’t have any expertise in this area but had won the work anyway. If that’s happening, what decisions are going to be made about those locations? The operational staff are so dedicated but they require more help and better management and procurement to solve these issues.

RN: Where there are sighting and safety concerns, trains have speed restrictions.

MG: Speed restrictions are the worst-case scenario for the rail industry. They’ll try and avoid those of course. What they’ll rely on is measures like additional telephones or whistle boards and they might implement a short-term emergency or temporary speed restriction.

RN: If Network Rail want the trains to go fast, and they want trains going closer together, they want increased capacity, then the fatalities won’t even come into it for them.

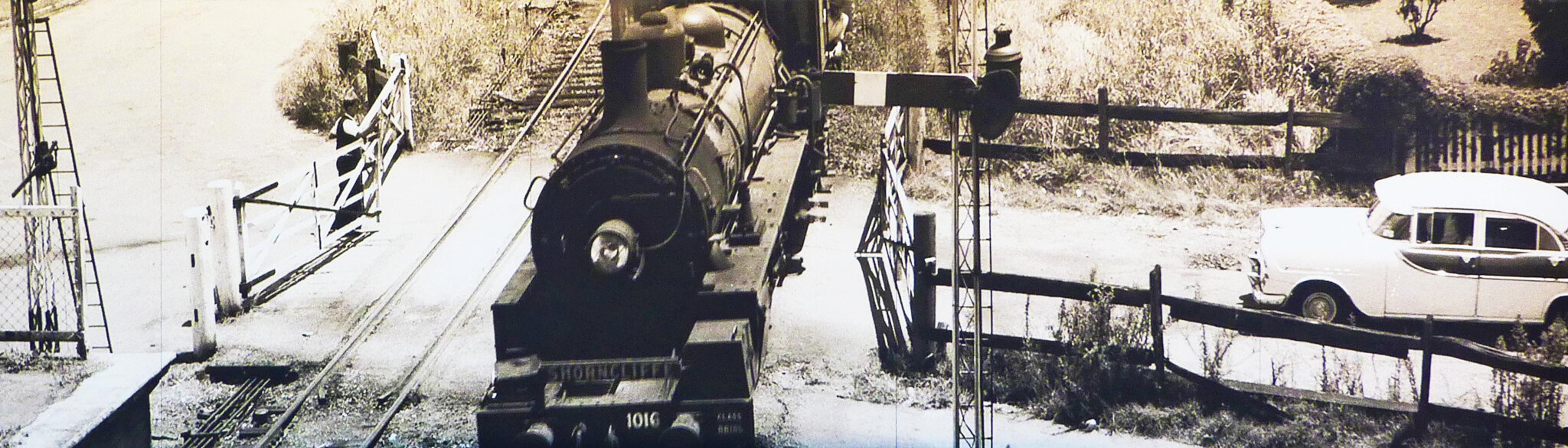

MG: That’s why it’s a mistake to only use the safety argument. You could say ‘Look, we’d just like to run all our trains at line speed rather than have this issue of having to slow trains down.’ All those things are recognized, but not enough is done about it. Network Rail would say, ‘we’re doing things. We just put out a tender for a warning system, even though it’s going to take three years to develop…’ But the reality is that level crossings haven’t changed the way they look in a hundred years; 4000 unprotected crossings across Great Britain haven’t changed at all. Go to them, look at them, they haven’t changed. People are still being asked to traverse, cross railway lines without warnings, with trains travelling at over a hundred miles an hour.

RN: What surprises me is that this isn’t just a British problem with its rail system. There aren’t examples where we could say, ‘Look at what Sweden is doing, that works really well. It’s cheap. Let’s do that.’

MG: In some sense you’re comparing apples with pears when you compare different countries. The safety integrity level varies. It’s very high in the UK. Other countries are more pragmatic. But in general most countries that have railways have lots and lots of unprotected crossings and, in general, there are very few solutions, and nobody’s doing a huge amount about it. And if you look at the work that we’ve done at the United Nations over the last four years, we are publishing a report that basically says the same thing.

RN: It sounds like perfect is the enemy of the good here.

MG: That’s exactly what it is. We want this high-level safety integrity solution that we can’t afford, but if you provide us with something that’s less than that but is better than nothing, then sorry, we won’t have one of those things. Part of the challenge is that the commercial staff and even the engineering staff do not feel the same pain as the operational staff. I can understand why a high level of integrity is required but all three elements have to work more closely together to provide solutions more quickly and more cost-effectively.

RN: Looking towards the future, do you think what’s really going to happen is either we have to get to a place where fatalities really start going up, or the system becomes so unworkable that at that point, they will spring into action, but too late?

MG: Probably your first point. There needs to be a tipping point. Back in 2005 in the UK, there was a double fatality of two young girls at Elsenham Level Crossing. And that drove improvements and changes over the next 10 years. Now, we’ve had a period of calm. Unfortunately it might take a high-profile accident before we see another huge amount of activity that says, ‘this isn’t good enough; we have to do something about it.’

RN: Prior to this I had thought of level crossings as always having barriers and lights.

MG: And people will identify with what they’re familiar with in their own local environment. If people knew that there were all these unprotected crossings where you have to put on speed restrictions and you have to put in whistle boards, that you have to rely on so many possible errors in the chain not happening: whether the train driver remembers to sound the horn, whether the person hears it. There’s even a ban on the times you’re allowed to use that train horn. You’re not allowed to use it between 11pm and, now, 5am in the morning. And there’s no formal protection. People would say, ‘Trains don’t run then.’ Oh, but some do. And some people walk their dogs at 4am.

RN: There would be no need for a ban on train horns if no trains were using the lines, because what noise would you be banning?

MG: More people work in shifts these days. If you decide to walk your dog at a whistle board crossing at 4.30am, you’d better hope there’s no engineering train or an early service or a freight train.

Let me give you another example. On certain lines, you have crossings that are manually-operated by the user. They have no protection; they’re just gates. You drive up with your vehicle, and you’re required to open the first gate. You have to then look to see if a train’s coming. You walk across the railway line and you go and open the far gate. And then you have to turn around, look back, see if a train’s coming to cross back and go and get in your vehicle and you go through the whole process again, closing the gates. In some of these locations, a telephone is provided for you to speak to the signaller, to ask if you can use the crossing. Most people would presume that what the signaller is doing is checking to see if there’s a train in the area before giving you permission to cross. But these crossings are often in what we call ‘long signal sections’. There’s no way for the signaller to know where the train is, other than knowing it’s in that section. So he can have a 10-mile section of track where he has no capability to identify where the train is exactly. So you get people using these telephones, and the signaller says to them, ‘Has the train passed you yet?’ The person says, ‘No.’ He says, ‘Well, you have to wait till the train passes you before you use the crossing.’ And then they’ll say, ‘How long will that be?’ And the signaller will think but probably not say, ‘Oh, I don’t know. I don’t know where the train is.’ As a result people who regularly use those crossings don’t bother to use the phones because they don’t get back any useful information.

People who do use the telephone at the crossing, maybe a first-time user or somebody who’s really compliant, experience high levels of frustration, because if you read accident reports, people report waiting times of over 15 minutes for a train to arrive. They’re sitting in their vehicle, often a commercial vehicle, maybe delivering something to a local factory on a Friday afternoon. They’re being asked to sit there on a single-track railway and wait for 15 minutes for a train to pass, even though they’ve called the signaller and asked for some useful information to help them cross; and then, to sit there again for another 15 minutes, 5 minutes after they’ve dropped off their delivery and wait for the train to pass again. At a place called Sewage Works Lane in 2010, the driver decided not to wait; he crossed the railway line and he derailed the train. People wouldn’t believe that there’s no technology better than a telephone with somebody at the end of it saying ‘Wait till the train has passed.’

RN: I suppose people get frustrated after waiting for 10 minutes and then decide to cross, increasing their risk further because the train is now much closer.

MG: That’s exactly what happens. Occasionally, the signaller makes a mistake; and says, ‘It’s okay to cross.’ There was an accident in the East of England last May, where the signaller appears to have given some incorrect information and the train struck a vehicle on the crossing. These things happen and it’s not that unusual. Most people don’t know these things and they think that a country that’s spending 70 billion pounds on high-speed rail wouldn’t have the methods of operation at some of the highest-risk locations for train derailment and multiple fatalities in the country – rail crossings. They are Network Rail’s biggest area of corporate risk, because they’re the only very predictable place where you have that high level of multi-fatality accident train derailment.

RN: Speaking of high-speed rail, what systems get put in place there?

MG: It’s very unusual for any new railway line to include a rail crossing, because at that point of design, it’s much less expensive to include an underpass or a bridge. They’re being designed out. The situation becomes unaffordable when you have crossings already on residential streets because you’d have to buy all the local businesses and houses to build an underpass or a bridge.

RN: I suppose the ‘positive’ then is that the number of level crossings at least isn’t going up.

MG: Yes, but the overall risk will go up and what will happen is that there will be a high-profile accident, and suddenly there will be a major focus on it and they’ll be asking people like me and everybody else; the media will be saying, ‘What do you think about this?’ We’ll be saying, ‘We’ve been telling Network Rail for the last 20 years that this is a massive problem, a legacy issue that they’re storing up.’ But, like I said, the solution has so many interdependencies; because it doesn’t just require Network Rail to decide that ‘we’re going to do something’ in safety terms. It also requires them to look at their procurement processes, their commercial processes, the timescales for introducing technology, their policies around the types of technology they use, their capability to try and understand different technologies; because the rail industry is very conservative, and most of the engineers in the rail industry are signalling engineers. I’ve been asked why I didn’t solve this when I was at Network Rail. The answer to that is simple. We spent three years improving the organisational capability to enable this risk to be managed more effectively. Creating the post of level crossing managers, removing paper-based systems, cleansing data, introducing mobile working and training for staff, closing crossings and introducing incremental improvements. This drove risk down by over 30%. The next step was to develop more technology solutions for the toolkit. Priorities changed and the focus fell on closing a relatively small number of crossings rather than looking at how to improve the majority of crossings that remain.

Signalling-based solutions are too expensive to be pragmatic or practical for most rail crossings, because of the whole life cost of them, because they’re expensive to design, they’re expensive to install and they’re expensive to maintain. But the reality is Network Rail doesn’t have the capability in-house to look at other disruptive technologies because their engineers are not experts in these technological fields. Most of these crossings don’t have mains power. They say, ‘We can’t get power to those locations, so we can’t put anything in there.’ Everybody’s using renewable power solutions these days, but again, it’s not an area of expertise or capability for a signalling-based organization. So when you start to unveil all of these layers of the problem, it’s a big thing to address. The problem is that the culture is very defensive. Objective challenge, particularly from outside is viewed very negatively. Challenge from inside generally results in a career choice. It’s a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy; a lack of challenge results in a lack of innovation and change.

RN: It sounds pessimistic.

MG: Yes, and we haven’t even talked about road crossings. Already at some locations during peak times, the barriers are down for more than 45 minutes per hour. What are Network Rail going to do when they’re running more trains? What are we going to have, 55 minutes in the hour; for these crossings to be closed? And you know the type of automatic crossing that they use — half-barrier crossings at many of these locations — the rail regulators already said ‘There are over 500 hundred automatic half-barrier crossings on our public roads. We do not want to see you renewing those high-risk crossings “like for like.”‘ But Network Rail don’t have any other solution other than a fully controlled crossing and that will often mean new signals and millions per location. They’re half-barrier because they’re fully automatic and not monitored so there would be a risk of trapped vehicles or people in the crossing if you closed off the whole road. Another area, another massive problem and it keeps happening. There is only one approved supplier of obstacle detection systems for crossings. The current network strategy relies on the removal of manually controlled crossings and replacement with OD crossings – but the current and only approved supplier has failed to make it through the pre-qualification for supply of the next 400 systems. However, there is an ongoing delivery plan and there will be a sizeable gap for development and acceptance processes between now and the next generation OD being available to operational staff to use. So presumably Network Rail will continue buying and installing systems that have failed to even qualify to be invited to tender stage. There is also the issue of the proposed closure of the Honeywell factory in Germany in January and any ongoing support for the current 200 odd systems procured.

RN: Surely, it would be cheaper and easier if this was sorted it out in advance.

MG: Yes, unplanned expenditure is the most expensive part of expenditure. That’s what will happen if a train derails in a location with an unprotected crossing. Or an issue with somebody not using the telephone, the Rail Accident Investigation Branch will, this time, make a recommendation to the rail regulator that says, ‘Network Rail will need to develop a solution to this now.’ And maybe, if it was really highly political, they’d go back to crippling speed restrictions.

RN: If this became acute because of a major accident, surely there’d be extra funding from the Government as well.

MG: The funding would be made available, I am sure. There’d be some pressure put on Network Rail to find or reallocate budgets, but in general, the funding wouldn’t be an issue. What would be an issue is actually delivering the solution in any kind of time that was acceptable to the train operators, for example, who would be having to reduce services or whatever the impact on them, as well as the safety side.

Martin and I concluded the interview there. Having delved into this issue with him, I was left somewhat speechless. Not in the sense of shock as such, but just with a ‘well, it is what it is’ fatalism. I can see why level crossings haven’t been tackled. It seems like a problem that’s not straightforward or simple to solve and one that requires a lot of co-ordination and collaboration between many big organisations. It’s just easier to reduce the number of hours a train can’t use its horn at night and call it progress. Especially with legacy issues such as level crossings. People aren’t dying. It’s easy to bury our heads in the sand. And this isn’t even an issue specific to level crossings. The rail industry as a whole is so slow to change. Even the most passionate advocates of innovation and improvement can be worn down by the resistance to doing things differently. The barriers to change just seem insurmountable when the only barriers that should be insurmountable are the ones on level crossings.